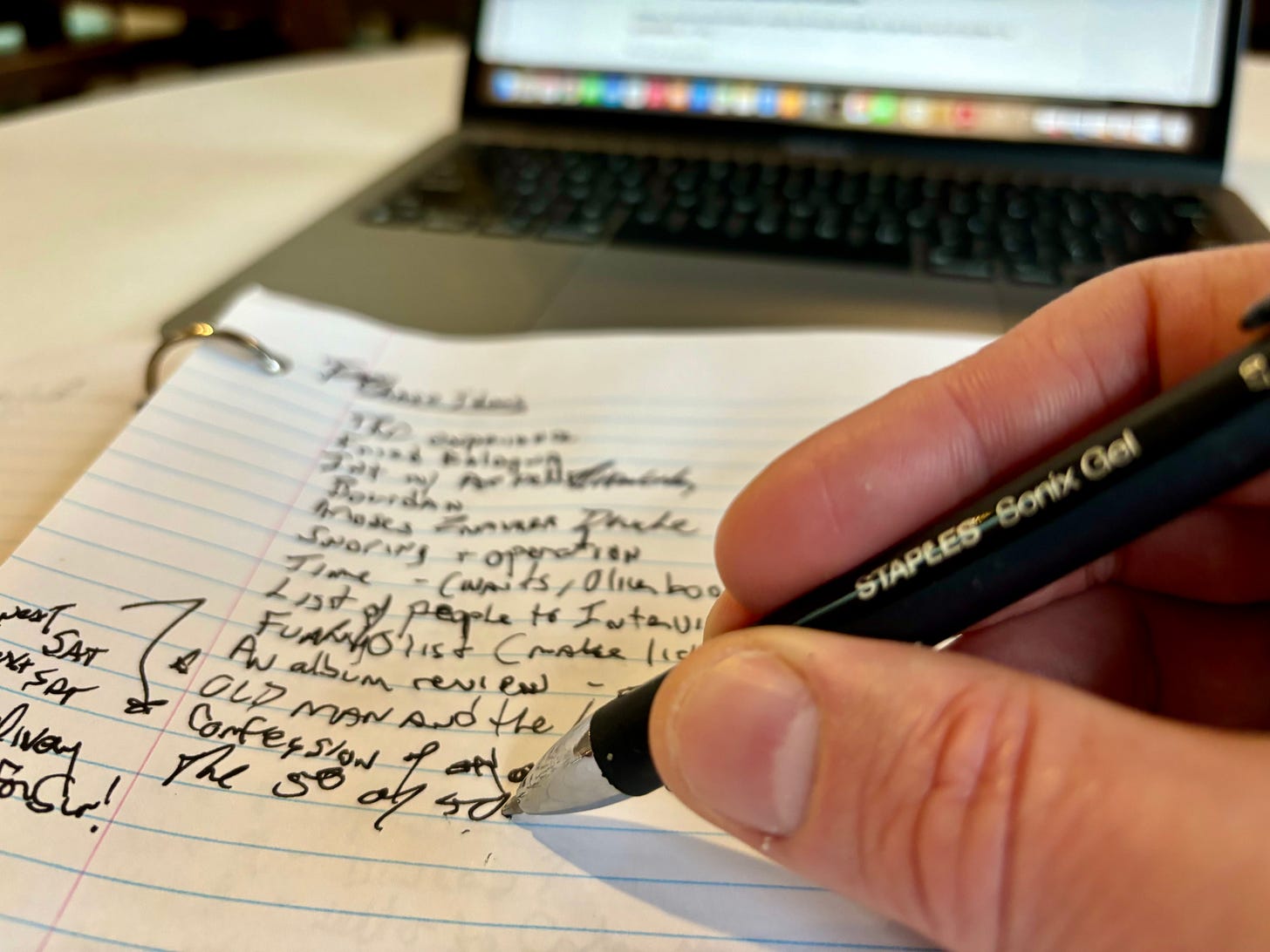

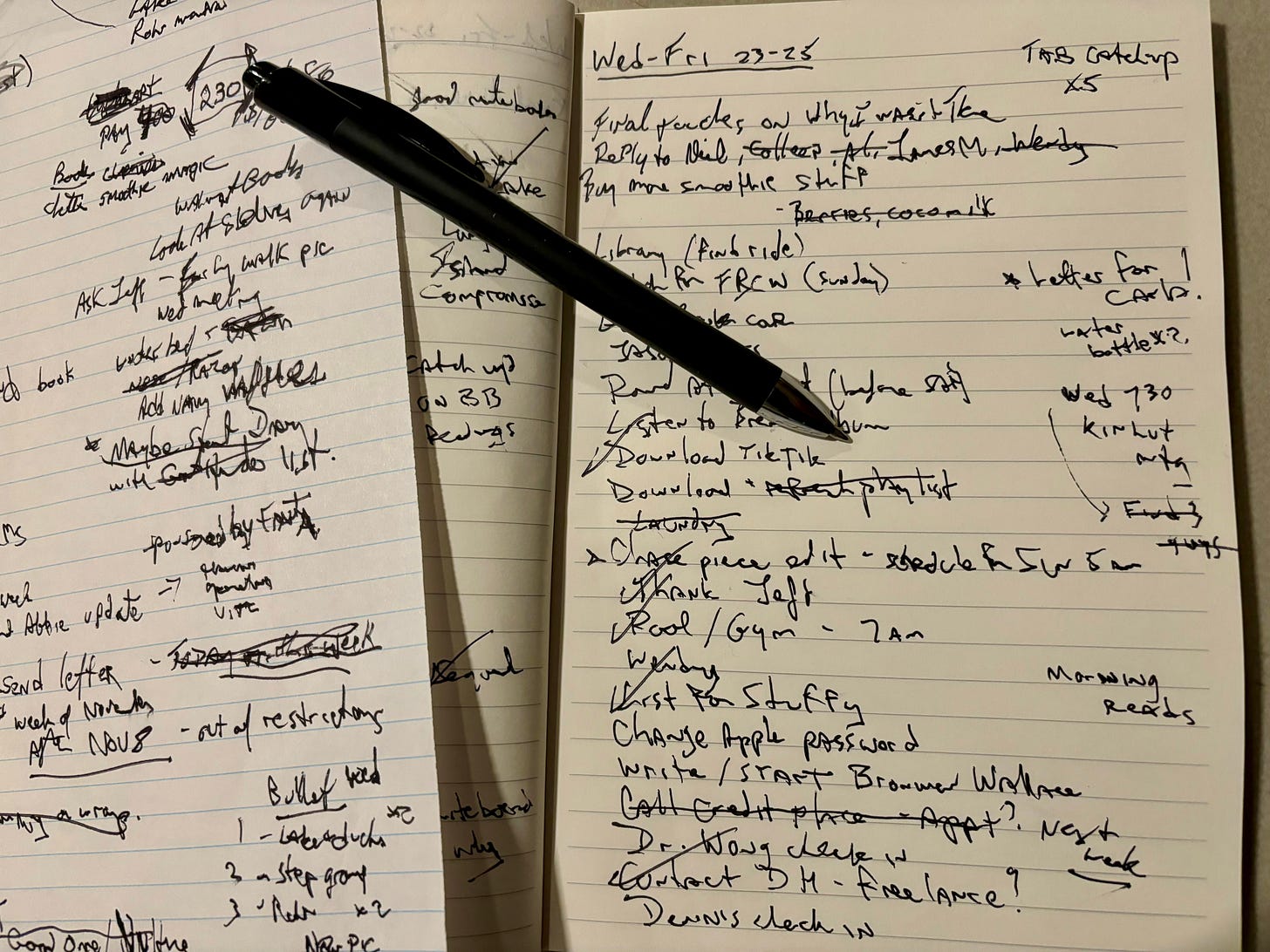

Since forever, I have written lists. I’ve even written lists of lists to make. I write lists in a dozen different notebooks, on scraps of paper, index cards, and long scrolls of brown paper towel from the men’s room.

I make to-do lists throughout the day. Lists of TV series and songs to stream. Lists of books to buy and borrow. List of essays and articles to read. Grocery and gadget lists. Lists of loves and regrets. Lists of jokes, side hustles, and people to reconnect with. And lists of themes to write for The Chase (today’s topic came from that list).

I suppose it’s my version of doodling or fidget-spinning while sitting restless in meetings, cafes, and bed. List making is also a futile attempt at having a sense of control and productivity.

It’s true that crossing off items can trigger a tiny dopamine kick, but chronic list making is a dangerous dive into the pits of perfectionism and procrastination — unfavourable, chaotic traits. In fact, right this minute, I’m itching to scribble a list of all the drawbacks of scribbling lists.

Yet there is substantial research that sheds positive light on writing lists. “When we create a roadmap to help us reach a goal, we are more likely to attain it and more likely to focus better on other areas of our work or lives in the interim,” according to the Harvard Business Review.

Better still, the fact that I prefer paper over any productivity phone app (such as Todiost, Tick Tick, Google Tasks) is progress itself. “The medium does matter,” according to technology journalist Nicholas Carr. “A book focuses our attention, isolates us from the myriad distractions that fill our everyday lives — a networked computer does exactly the opposite.”

No matter how I spin this habit in my favour, the fact remains that I still make a lot of lists. I need to examine why, and how to rein it in.

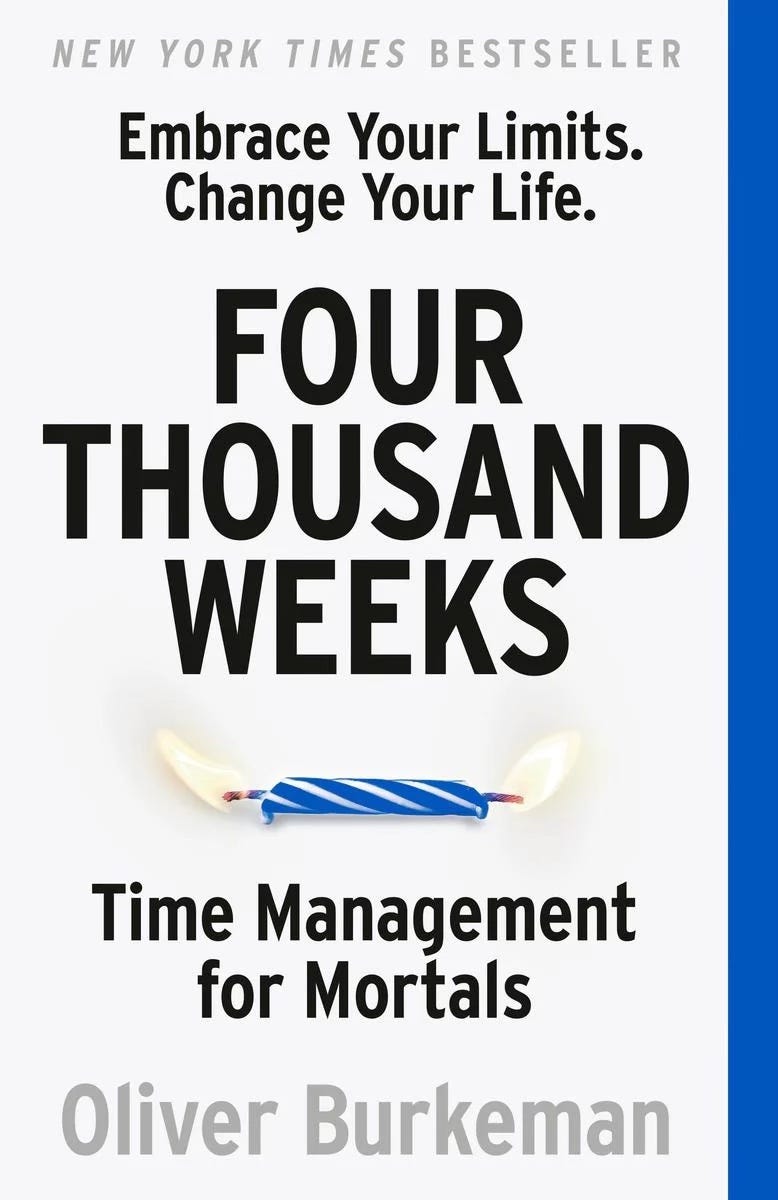

My list reframing came from a book I received in the mail. After ranting to him about the 100-plus unread tabs open in my browser, my buddy Steve Pratt (of The Creativity Guild) sent me this:

Oliver Burkeman gives the finger to the pile of productivity books that preceded his; Four Thousand Weeks (the dispiriting estimate of how much time we live) is the author’s argument that we can never master time management or make lists to better our lives and achieve happiness.

Burkeman writes that there will always be too much to do, and we can’t avoid tough choices or make the world run at our preferred speed. “Entering space and time completely — or even partially, which may be as far as any of us get — means admitting defeat,” he says. “It means letting your illusions die.”

When Burkeman asks if we “are living too much in the future at the expense of now?” I knowingly nod at first, like I’m in on the theory. Then I sink in my chair when I realize he’s talking about me.

Living in the now isn’t a novel idea — ancient spiritualism, stoicism, and every meditative practice have the copyright on that shtick.

Burkeman covers the need to live in the present nicely, but goes further to hammer home the relief we feel in understanding our insignificance; to know that we’ve been holding ourselves to standards we couldn’t reasonably be expected to meet.

“Once you’re no longer burdened by such an unrealistic definition of a ‘life well spent,’ you’re freed to consider the possibility that a far wider variety of things might qualify as meaningful ways to use your finite time,” he writes.

I realize when reading this, that my wish lists — scratched in black and white — are way more colourful than life I’m actually living.

And I suddenly feel…listless.

I’m never going to end making checklists, because checklists themselves are endless. The larger the list, the shorter the path to pressure and disappointment.

So I’m currently experimenting with some productivity frameworks to harness my habit, like the pomodoro method of breaking tasks (like writing) into 25-minute super-focused intervals. And I particularly appreciate the 1-3-5 technique: completing 1 major, 3 medium, and 5 small tasks each day.

I also made a list of 5 changes I’m implementing immediately:

Prioritize to-do tasks, time-block, and list longterm goals

Maintain a flawless marriage, career, and physique

Earn a half million by St. Patrick’s Day

Save a kitten from a fire every fortnight

Set realistic goals

OK. Clearly, I need some work. But I plan on filling the rest of my 4,000 weeks with more than list making. And that I can check off.

So many lists is dispiriting and also self-defeating. I am also something of a perfectionist and find that confining my lists to my head is helpful. There’s only so much the average human can carry around in their head so the lists self - limit after some mental triage of what’s immediately important.

Ultimately, all those lists are only overwhelming.